A Site of Historic Proportions

The Mermaid is a declared California landmark with a diverse and notorious history. Past identities include: country club, youth camp, gangster gambling house, gay nightclub, and celebrated concert hall.

• 1930 - Built as The Sylvia Park Country Club. Noted architect, Charles E. Finkenbinder.

• 1930s 40s - Youth retreat called Rancho Topanga.

• 1940s - Gambling house and brothel operated by Los Angeles mobster, Mickey Cohen.

• 1955 - 1972 - Reborn as a gay nightclub called The Canyon Club, run by former vice cop.

• 1972 - 1977 - Celebrated artist’s haunt and concert house called The Mermaid Tavern.

• 1980’s - Structurally unsound from years of neglect, nearly demolished.

• 1990 - Purchased by Topanga artist, Bill Buerge, and restored to it’s former magnificance.

• 1993 - Declared a California state and LA county Point of Historic Interest.

Today, the Mermaid is a horticultural retreat for the rejuvenation of mind, body and spirit, and for the celebration and preservation of our irreplaceable architectural, cultural, and natural heritage.

To Rescue a Floundering Mermaid

She was originally built in 1930 as the Sylvia Park Country Club. In the 40’s she was reinvented as a gambling house run by the infamous gangster, Mickey Cohen. In the 50’s she was reborn as The Canyon Club, a gay night spot owned and operated by a former vice cop. Other assorted identities include American Legion hall, Jewish boys’ school, theatre, and a celebrated concert hall called The Mermaid Tavern. By the late 1980s, the place was an exercise in deferred maintenance, a ship wreck in slow motion listing precariously, with a crumbling foundation, a checkered past, and an uncertain future. In 1989, a local artist with a passion for old houses and history bought the property, moved in with the rats, bats, and one feral cat, shoveled the horse manure from the floor, and began a twenty-year journey of rebirth and rehabilitation.The Mountain Mermaid is now a horticultural retreat for the rejuvenation of mind, body and spirit, and for the preservation of our natural, architectural and historical heritage.

The rest is history.

—————————————

Story below excerpted from the Topanga Messenger, July 1999.

By Bill Buerge, Owner

The real estate ad read, “Original 1930s Spanish Colonial full of interesting history, a rare opportunity, the ultimate fixer-upper, not for the timid.” I had seen the Mermaid for years from the outside. When the agent showed me inside, I was hooked. Legend has it that mermaids would sing irresistibly, causing sailors to fall overboard in love with them. Like those hapless sailors, I was mesmerized by the magic of this magnificent building. I could not sleep for days thinking about her. Aside from the astronomical asking price and being structurally unsound, there was one minor detail, the Mermaid had already sold. She went rather quickly. She was in escrow. I had to have her. I made a backup offer.

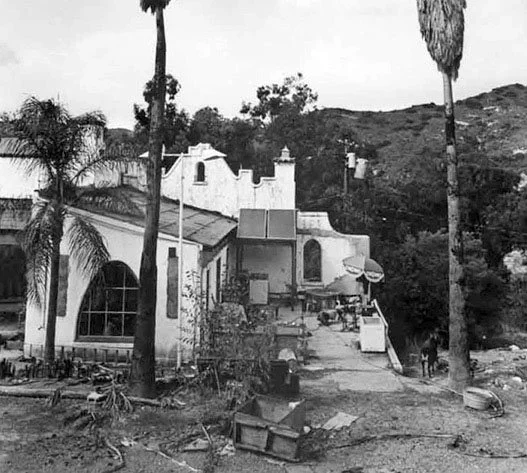

This pre-renovation photograph was taken by local photographer, Dede Warpole, and given to the new owner after he had moved in. Trash littered the site,the building listed different directions, and dark burn marks from previous wildfires marred the palm trees. Calico, the document-eating goat (seen at the base of palm at far right) came with the place.

The buyers in first position conducted their inspections. There was bad news. One could walk around under the structure and view the 100-foot long retaining wall and rows of timbers supporting the building. It was a chamber of horrors. Everything was buckled and leaning sideways to a degree that was truly terrifying. The place was going south — and fast! A totally new foundation would be needed asap. The fireplace was gone, the roof was a joke, and the County would require she be brought up to code with new electrical, plumbing, heating and a seismic retrofit. Most of the windows and doors were shot. Basically, she must be totally rebuilt. It’d be cheaper to tear her down and start from scratch. The buyers balked and backed out of escrow. My offer was accepted.

Buyer’s remorse filled every corner of my being.

I was awash in doubt. I had made a big mistake. Where would the money come from to fix everything? Where would the big down payment come from? I could lose everything. This Mermaid would eat me alive. I proceeded with my inspections.

Winter came. It rained a lot. Everything leaked. I couldn’t wait for escrow to close so I dug trenches to drain water away from the foundation, and I remedially repaired the roof. I hired an aerial survey company that flew over the site, took pictures and created a topographical map. Having a map with measured elevations would be essential in preparing the drainage plan required by the County.

Getting the big down payment together was a squeaker. I put quick-sale prices on two pieces of property I owned and listed them with brokers. They sold! Now there were three escrows pending closure.

Finding a lender was challenging as well. The Mermaid was a diamond in the rough. She got a paint job and was cleaned up to look her best in the appraisal pictures. A bank agreed to do the loan without even coming out to take a look. It’s probably a good thing. It took over four months to close all the escrows. I moved in January of 1989.

Then it snowed. A solid sheet of ice formed atop the expansive flat roofs. It melted slowly, percolating a roofing-compound-colored brew, Mr. Coffee style, into the rooms below. Everywhere inside I erected elaborate plastic catch-basins to collect and deposit the water into containers that were emptied frequently. Record-breaking rains followed. I set up measuring devices to track the movement in the foundation walls. In horror I observed the cracks grow into gaping fissures. My repairs were useless. I called out an official from the Building Department. He classified it an emergency.

Like her mythical sisters of the sea, this siren called to me. After all, that was what she had been designed to do. She was conceived as a calling card, as the centerpiece of a country club and set in 1930 like a gem into the rustic hills above Los Angeles. The builders subdivided the land around her into hundreds of tiny weekend cabin lots. Her job was to entice folks out of the city below up here to purchase land and get a free club membership as part of the deal. They named her the Sylvia Park Country Club after a beloved daughter.

Their timing was not terrific, however, and the ensuing Depression brought this country and the country club to a screeching halt. They concocted wild schemes to try to turn a profit, including constructing a full-size oil well in the backyard. Public relations pieces were printed to mimic newspapers with headlines heralding the imminent discovery of oil and subsequent increase in the value of the club memberships. No oil was ever stuck, but ground water was. Later the well became a little water company that until recently serviced a handful of homes in the area. Sales languished. So the builders minted coins and scattered them around town. The coin-holders were entitled to trade them in for a free lot at the club. There was a hitch. Either the lots were unbuildable cliffhangers or undisclosed fees were involved, or both.

In the 1940s, the name was changed to Rancho Topanga, and the property was sold. During the war it was a clandestine casino and sometime brothel operated by the notorious mobster Mickey Cohen. Fancy ladies lounged upstairs in the ballroom, available for dancing and more if you paid the price. In the 1950s it became a Jewish boys school run by a rabbi and for a while an American Legion Hall.

In 1960, an enterprising former vice cop named Phil Ewing purchased the still-beautiful building and open a gay bar, calling it the Canyon Club. He pillaged the building of its historical artifacts, removed the roof tile, attached metal sheds on all sides of the building and covered up the spectacular wood ceiling in the ballroom with corrugated plastic. Truckloads of the original Monterey furniture were given away or hauled to the dump.

In 1972, she was sold again and reborn as a celebrated concert hall named the Mermaid Tavern. World-class musicians played there weekly. Guests loved the Mermaid Tavern’s bohemian elegance. They would skinny-dip in the pool in the early evening and later dine in the grand ballroom and listen to the magic.

By the late 1980s the Mermaid was a shipwreck in slow motion. An exercise in deferred maintenance. A ruin. During the wet months she’d flounder hopelessly in that indescribable Santa Monica Mountain goo experts call expansive adobe soil. Ensuing hot weather would bake the soil as hard as bricks. This soil type can wreak holy hell on foundations over time with all the back and forth-ing. The Mermaid’s old cement footings were too shallow, lacked steel reinforcing, were cracking up badly and leaning over. Rivers of misdirected runoff raged through and under the foundation. Like the Titanic, her massive bulk listed in two directions, and she was literally breaking in half. A small earthquake could surely take her down.

Much of her skin had fallen off when I got there. Piecemeal, great plaster shards would crash down, unannounced, like glacier ice sloughing off into the sea. Nature was taking her back. All manner of flora and fauna had moved in before me. The bees and termites had been exterminated during escrow.

The day I moved in, horse manure lay on the floor amidst piles of the dead bees. Bats were literally in my belfry. I lived for a number of years pretty much in one room in the tower part of the structure. I’d fall asleep at night often hearing the bats circling a few feet overhead. Eucalyptus roots had burrowed their way 50-feet under the house and were growing through the shower floor to get a drink. Wood everywhere was rife with rot and termite damage. Rats ran inside the walls via a network of rodent roadways.

I grew accustomed to living on the edge. Mostly I felt challenged and extra alive. There were, however, some low moments living in this waterlogged unsafe hulk of a former country clubhouse. Water was my constant companion and nemesis. One time rain got in and reduced a mountain of unpacked moving boxes into a soggy lump of paper pulp. I lost some fairly irreplaceable stuff in that one. I achieved my lowest ebb, however, when rain invaded the attic above my living quarters. The ceiling suddenly opened up, depositing a truckload of rotten plaster laced with pigeon poop into the room. I cried.

Back to the foundation. There were the usual time-consuming soils and geology reports, engineering calculations and plans to be submitted. I did my own architectural drawings and consulted at length with a historical architect. It took six months to get the permits. I got bids from contractors and several house-moving companies to fix the foundation. The latter specialized in shoring up and straightening up old buildings. Eventually I assembled a crew consisting of a wily and wise semi-retired contractor named Jerry Stark and a number of other workmen. Juan Calles, the current chef at Pat’s Topanga Grill was on the team. I owe a lot to him and two other tireless team members, Stevie and Sergio. The value of their contribution is incalculable.

A section at a time, we went around the perimeter, first shoring up the house and then digging out the old foundation. We would excavate down to competent bedrock, as much as 12-feet as verified by the soils engineer, build forms and pour or build new concrete block foundation footings and retaining walls. Sometimes Gunite was used. Some steel and laminated wood beams were installed. Measures were taken to preserve the original floor plan and integrity of the historic fabric of the structure. The old foundation ended up a mountain in the front yard. It took 35 trips in a big truck to haul it off. The structure was brought up to current earthquake standards with an extensive assortment of tie-down bolts, metal straps and other specialized hardware. New and some antique doors and windows were installed along with new electrical, plumbing and heating systems. Ashes from the fireplace had collected for decades inside a brick chamber 10-feet tall under the hearth. We carefully sifted through the ashes, finding many well preserved articles of historic interest. The fireplace was then rebuilt. Rotten wood was replaced. Walls were straightened, strengthened and insulated. Some exterior plaster was saved. Most had to be replaced. New drywall was installed on the interior walls. New wall surfaces inside and out were textured to match the old and painted. The antique floors were renovated and refinished.

I wanted a bullet-proof, leak-free roof. I contacted the office of the California State Architect for help and spoke with a historic specialist. He came out and told me exactly what they did when replacing roofs on the California missions and other old buildings. I visited the company they use to fabricate their replica roof tiles. In their yard they had a big stack of handmade tiles left over from a mission restoration. I purchased them for a dollar each, an incredible value, and had them shipped to the Mermaid. A roof engineer redesigned all the roofs. Subroofs were replaced or reinforced and waterproofed. The new tiles were then installed. The pool had been abandoned, filled with trash and buried. It had cracked in half like the Mermaid. Its back was broken, as a visiting pool consultant put it. Excavating out the trash was a bit of an archeological dig, yielding some interesting old documents, a motorcycle and a swamp cooler. A decomposing smelly black ooze was at the bottom. We engineered and rebuilt a whole new, massively reinforced pool inside the old shell. I applied colorful tile at the water line made by Topanga ceramicist Rebecca Andrews.

Early photographs showed the premises festooned with an artful array of wrought iron grillwork, tile, light fixtures, wall hangings and Monterey furniture. It was all gone except for a singular water-damaged table. I had it rebuilt and collected and installed old lights, gates, doors, tile and furniture from the period.

I discovered a huge passion for gardening. I immersed myself in the plant world, read books, attended landscape conventions, joined clubs, volunteered at the Huntington Botanical Garden’s cactus and succulent section and worked together with landscape designers on a plan for the Mermaid. The plant list included drought-tolerant California natives, cacti and succulents, grasses, palms, bananas, canas and birds of paradise. The acre surrounding the Mermaid was graded, sprinklered and planted over the past six years with untold pickup truckloads of new and donated trees, shrubs and flowers. I developed a morbid fascination with “The Money Pit,” a movie featuring Tom Hanks getting financially and literally consumed by an old house restoration. I watched it a lot. I must have identified with his plight.

The Mermaid had a history of financial hardship. The Country Club and the Mermaid Tavern both were financially challenged enterprises. Midway through construction, I ran out of money and sat with a half-finished Mermaid for over a year. A dozen lenders turned me down. Banks hate half-finished projects and rarely loan on them. Then I learned the hard way about hard money, that bad- boy of the loan world. There were these two men who loaned to people in emergency situations who were desperate or dumb enough to pay 40 percent interest. Namely, me. I swallowed hard, signed the papers and finished the work sufficiently enough to pull a certificate of occupancy from the Building Department and therefore qualify for a normal loan.

At another point I was at a financial dead end and listed the Mermaid for sale. It was an agonizing decision. But the bottom had fallen out of the real estate market. I couldn’t get a loan, and foreclosures were the order of the day. Sharon Stone and Diane Keaton looked at the property. The place was pretty torn up. There was a lot of interest but no offers. Eventfully I took it off the market and recommitted to finishing the place no matter what. Since the Mermaid is now more presentable, it is not unusual to receive unsolicited offers from interested buyers.

Assembling the Mermaid’s historic record has been an abiding fascination. I was amazed at the truly astonishing array of past lives, job descriptions, make-overs and name changes. The neighbors related stories. I tape-recorded Melvin Penny’s account of the pool construction that he worked on. One earlier owner of the Mermaid stopped by and told how he personally dug out places in the dirt basement to put slot machines. One afternoon Sylvia’s son Alan Patterson showed up at my door. His uncle and grandfather were the original builders. Last fall a man from Florida called, named Mel Mobray. He was in the Navy in the 30’s when he bought some Sylvia Park lots. He still owns them and sent me an old brochure from the country club with detailed photographs of the whole place and an artist’s conceptual rendering.

Another neighbor, Celeste Fremon, unearthed artifacts from the country club while excavating the foundation on her new home. She says, “There’s an enamel-baked-on-metal disc with the Sylvia Park logo and a rusty pocket revolver. I think the gun belonged to one of Mickey Cohen’s molls… or else it’s a cap gun.” She prefers the gun-toting moll scenario. I learned of a local historian who did “house histories” named David Cameron. He did a series of reports on the Mermaid, digging deeper each time. The architect was C.E. Finkenbinder, who had other notable buildings to his credit and worked as a city building inspector before he died. The builders were brothers, Charles and Irving Goldman. Sylvia was Irving’s daughter, born in 1923. The Mermaid was a clubhouse begun in the spring of 1930 and finished 100 days later for a cost of $10,000. The whole country club complex was anticipated to cost $75,000. Mr. Cameron was very involved in the historical community. He helped me prepare reports and applications to submit the Mermaid for registration as an historical site. On August 6, 1993, the California State Historical Resources Commission voted the Mermaid a California State Point of Historical Interest, No. 058.

It’s been an honor to host benefits at the Mermaid. There was the fund-raiser for Topanga burn victim Colin Specht. The annual Midwinter’s Night Feast for the Theatricum has been a big success. Cheney Drive neighbor Gayle Scott and others organized an unforgettable poetry event to benefit the Topanga-based Mountain Aids Foundation. A film company shooting at the Mermaid made a generous donation to a neighbor living across the street, Mara Markin. She had cancer and could not work. It was the first deposit into “The Mara Fund.” Neighbors and friends gathered around her. The fund grew and helped sustain her during the last year of her life.

Living here has been a privilege and a pilgrimage into so many new worlds: historic preservation, the building arts, horticulture, creative financing. Architecture became my art form. I met or worked with faux finishers, house historians, pond people, feng shui practitioners, aerial topographers, cactus propagators, paint chip analysts, hydrologists, used roof tile dealers and spider wranglers.

The Mermaid’s been this amazing journey. An adventure. A challenge of a lifetime. An exercise in delayed gratification. A work in progress. A wild ride. A labor of love. I have gratitude for the people of this community, the construction gods and even 40 percent money when it’s the only game in town…for all the rich history and for the benevolent spirit that pervades my premises.